Recorded on Tuesday, May 26, 2020.

Introduction

Last week I posted about having finished the HSK Shang / Xia (上/ 下) books. I actually finished them a while back but I’m going through the grammar points once again, but this time with a teacher. Why didn’t I get a teacher in the first place? Because I didn’t want to get caught up on the vocabulary and all of the words I didn’t know rather than simply focusing on the grammar itself. That is to say, if I had a teacher last year when I started the HSK 4 books, then we would’ve been spending a lot of time on vocabulary rather than the grammar. Vocabulary I can learn on my own, but correcting grammar mistakes, as I’ve found, requires a bit more help, or, at the very least, a bit of outside motivation in order to get it right.

So, today I thought I’d share with you all about how to learn a language.

I’ve learned a few: Ukrainian and French throughout my childhood; Latin and Ancient Greek in university, Korean while in South Korea, some Russian, but only because it’s so similar to Ukrainian, and now, since I’m living in China, almost as if it’s a “revenge” of sorts for not focusing on any other language before, I’m learning Mandarin Chinese.

A bit about Mandarin Chinese

Mandarin Chinese is different from Cantonese, which is spoken in the southern parts of Mainland China, particularly Hong Kong. Further, Cantonese uses Traditional Chinese characters whereas I’m learning the simplified characters used on the Mainland. What’s the different? The Traditional characters have more strokes per character and, more importantly, are pronounced far differently from their Mandarin equivalents.

Mandarin Chinese has been the hardest language I’ve learned to date as it’s required the most time and effort. But it’s not just the language, it is my focus on the language and in using it here in China. I’m getting better, even though some people say my tones are off, and surely my Chinese grammar is not so good.

What does it take to learn a language?

I wrote a blog post a couple of months ago about some things to keep in mind when selecting and beginning to study another language. Those factors included an interest in what you’re doing, relevance to your life, work or other goal, and the ease with which you can actually accomplish your goals.

How to learn any language

These aren’t revolutionary ideas, but they are necessary in order to gauge your own progress and your expectations of progress.

If you’re not interested in learning the language and, more importantly, using the language to learn more or interact, then you will struggle putting in the time necessary to move beyond the basics and into the intermediate and advanced levels.

Likewise, if the language isn’t relevant to your needs, you’ll have difficult maintaining focus and maintaining discipline.

Finally, if it’s not easy for you to accomplish these things, then you’ll find that you’re struggling to simply get something done rather than spending the time actually learning the language. Whether it’s an APP that you have to download, an electronic dictionary, a website you have to access, or even something as simple as ink in your pen, you have to make things simple enough that you are spending more time learning your target language rather than fighting the tools that are supposed to be helping you.

How do you develop your language skills?

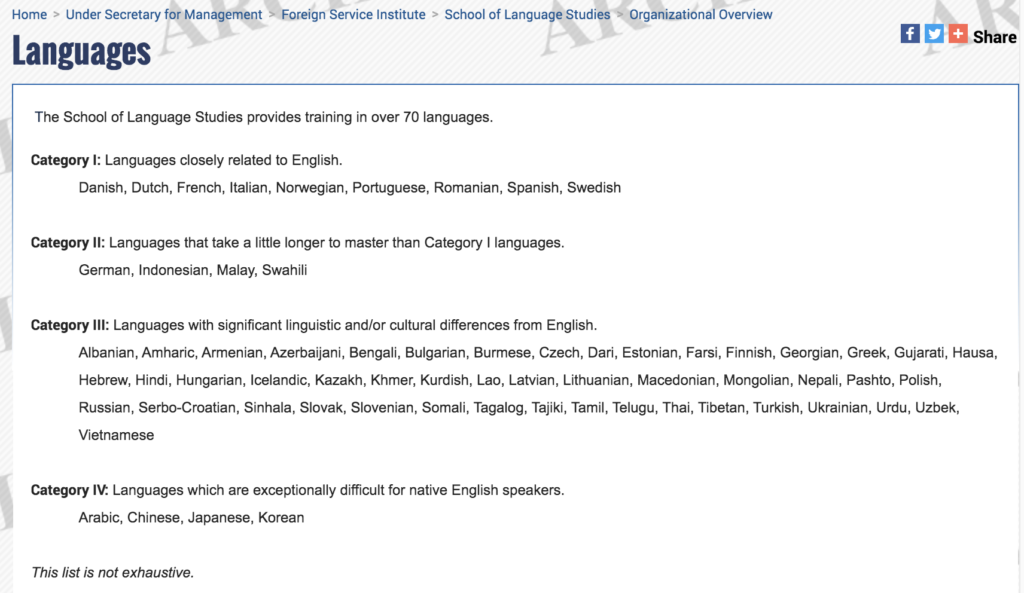

It should come as no surprise that each language has its own, unique set of requirements and its own learning curve. One of the departments of the US Military, the Foreign Language Institute, is a department The Foreign Service Institute, part of the US Department of State, is focused on teaching their staff how to learn and communicate in languages other than English. They’ve broken down the number of hours, on average, it would take a native English speaker to learn another language.

There are about five levels of language learning, ranging from “pretty easy” to “very difficult”. Languages such as French or Spanish fall into the “easier” category, ie, a language you could probably learn within a year if you dedicated yourself to it. The harder languages are those like Russian, Japanese and Chinese, both Mandarin and Cantonese.

This, of course, depends on your own ability to learn, to focus, to dedicate and to discipline yourself in your studies. If you don’t put in the time, you’re not going to get the results. And no, technology isn’t going to replace learning any time soon.

Technology has certainly made it easier, which is what I discuss in my blog post about learning a language, in that APPs and websites and cell phones have made it insanely easy to access, record, participate and study anywhere at any time. There really is no excuse.

Which language do you want to learn?

Is it for travel? If so, you’ll only need to know the basics, the numbers, some polite words such as greetings and saying “please” and “thank you”.

Is it for business? If so, you might need to learn more industry-specific terminology in addition to the formalities and nuances of politeness in your target language.

Is it to speak with a lover or your in-laws? Both will require a bit more of a conversational approach and won’t require as much focus on grammar and structure, but would require an effort on your behalf.

Or do you simply want to read books in another language (which is what a lot of people learn Japanese for), or is it to watch TV or movies from another country (such as French or Italian) or do you want a more global, probably spoken in most places type of language, (such as French, Spanish, Mandarin, or Russian)?

Once you’ve got your target language settled upon, it’s time to start digging in.

How to start learning a language

Read. Just start reading. Look at the characters and how they’re formed and how the sentences look. This is your first basic step.

The second basic step is to start speaking, to try to say the words and pronounce them as they seem to you. You’re definitely be re-learning your pronunciation as you go along.

Other than those two very simple and basic steps, you’re going to need materials, not necessarily a textbook, but easier materials for you to learn from. People often recommend children’s books but I tend to shy away from those mainly because, as an adult, you can’t derive as much from a kid’s book than you can from a newspaper in your target language. That is to say, the language will be overly simple (which is a good thing) but it’s of limited use.

Newspapers can be difficult but they are cheap and they are published online these days. So, in that case, they can be a good starting point.

Graded readers are also a good item to have a few of. Or even those dual language books, which are popular in French and Spanish and even Russian.

Keep in mind you don’t want to spend a lot of time trying to find materials, you want to make this easy for yourself. Use what you can and what’s available to you. Check out your local library’s resources, both online and off for what they have to offer.

And there are two ways you’re going to read: intensively and extensively.

Intensive reading means you’re looking up every single word and making sure you understand what they mean and what the sentence is trying to convey.

Extensive reading is focused on getting the gist of the passage and trying to cover more ground in a shorter period of time. I liken extensive reading to getting used to moving your eyes across the words and being familiar with how the language looks rather than learning the in-depth charactertics of the language, which is what intensive reading is.

Further, for intensive reading you’ll be making word lists. I used to use a pen and paper and, let me tell you, it was a pain in the ass keeping them all organized. Now I use AnkiDroid, which is free, or you can use AnkiWeb, also free. The iPhone APP, sadly, costs money. There are other programs, such as Quizlet or even Memrise which can help you build vocabulary lists and to simply focus on learning new words.

And new words are important, but you need to use them.

How do you use the language you learn?

Start writing and speaking out loud. Are you able to say the word you just read? Do you know how each of the words in your word list is pronounced? Can you make a sentence with each word or a set of words?

Collocations and phrasal verbs, common in English, will help you link together a lot of your words and make your sentences sound more “natural”.

Don’t go for “native”, go for “natural”.

What’s the difference?

Native means you were born and raised or otherwise immersed in a language for such a time that your brain and your mouth muscles are literally wired in that way.

Natural, however, allows for an accent (how many accents are there for English, French or even Chinese?) but the command of the language is the same. It doesn’t mean people will think that you don’t know the language (although that’s a common misconception) but your ability to work within the language, its framework, and to communicate in such a way that people would really have to think and listen intently to find out whether or not you were actually born in a country that speaks that language.

One obvious example is the Indian accent, from India. How many Indian immigrants have you met who have a thick Indian accent, you know the one I’m talking about. Would it surprise you to learn that an Indian-born passport holder can have a natural way to speak English? Yes, their British history might have something to do with it but there is also the command of the language itself that continues to this day.

Writing

But don’t force yourself to write paragraphs and paragraphs of epically brilliant prose in your target language, or even a movie review. Instead, you can take smaller steps along the way. For example: noun declensions or verb conjugations, think of Latin, French, Ukrainian, all have different genders, placements within a sentence (subject, object, use) or even different forms for the time aspect (present, future, past, completed and incomplete actions or even conditionals).

Just write.

As it stands, for Chinese, I have notebooks full of written characters. I now write all of my homework in Mandarin Chinese and rarely use pinyin if I have the time. By that I mean, if I’m in class and have to make a note I’ll still use pinyin so I don’t have to worry about the character.

Speaking

And as you write you’ll begin to formulate the images in your head, what the word looks like and how it should be written, but can you speak it out loud?

Ever have that problem of “I know the word but I don’t know how to say that”, there’s your disconnect between writing and speaking.

So, how to help mitigate this occurrence?

Write and speak out loud as you go. Think of a sentence, speak it out loud and write it down. Don’t worry about it being correct, that will come with time. Just focus on language production.

Getting a speaking partner would be great but a lot of the simpler stuff you can role play yourself. Need to buy a ticket? What kind of ticket? Need to ask for directions? Can you navigate yourself to work in your target language? Do you know how to make a phone call in your target language?

Grammar

And finally, more often than not, your grammar will suck. You’ll hear all sorts of people claiming that you can learn and master a language within X number of days but the two things that will hold you back are the depth of you vocabulary and the grammar you use.

Some people say not to study grammar at all and to only pick it up as you go along. After all, that’s what kids do. Or so we like to believe.

But, you can no doubt tell the difference between a person who has gone to school and a person who hasn’t, notice the difference in their sentence structure. I am not making a social commentary here, but I am saying very clearly that kids can learn the basics of the languages very easily, but refining the honing that language skill will require some form of education.

Now, do you sit there with a grammar book and just memorize it?

No!

Apart from your declensions and conjugations and your speaking out loud, you’ll need to find out what problems you’re having with your target language and how to fix them. You need at least one resource, and many can be found online these days in some form of a wiki.

Managing your time

Get a dedicated notebook and keep track of everything in there.

Get a stopwatch and a spreadsheet.

When you sit down to study, determine the length of time you want to focus and then set your stopwatch to go. I don’t use a timer but the stopwatch because I’m willing to go a bit longer or to stop a little bit shorter of my goal but I still want to record how long I’ve studied for.

Take that number and put it into your spreadsheet, write down what you accomplished or how much of the book or newspaper or characters you were able to get through on that day.

Split your spreadsheet up into different categories. This would include things like “Vocabulary”, “Grammar”, “Speaking”, “Listening”, and “Writing”.

Why so many? Because with each session you complete you want to focus on one thing. So, thirty minutes of listening is just that, listening to the radio or a TV program for thirty minutes, not worrying about grammar or even vocabulary.

Grammar – you want to spend 15-20 minutes only on studying a specific grammar construction, not thinking too much about writing or speaking it out loud, only the grammar concept and its application.

And so on.

Conclusion

That should be a pretty good list to get you going. Let me know if you have any trouble getting started and we can work something out. The important thing is to start the process, to begin, to take that first step.

I’ll post links to my articles on learning Chinese and Japanese that way you can have a look to see how my own studies took shape over time.

***

That’s is for this week! Follow me on Twitter @stevensirski