Christmas overseas, especially in Asian countries such as China, just isn’t the Christmas I grew up with. I grew up in a Ukrainian-Canadian household in which church played an integral role in our Christmas celebrations / holiday season / festivities / Christmas. Recall the “Christ” part of Christmas? Yea, my family took that part kinda seriously.

In any event, China has embraced the colours and gift-giving shopping experience that is so symbolic of the modern Christmas of the West. There are trees up around town, there are Santa Claus faces, seasonal sales and the traditional (and generic) USAmerican-Hollywood/New York-endorsed holiday carols playing over the loud speakers, all in an effort to “blend in” with the globalization that modern Christmas has become. I can’t blame them for using these things, but I also can’t say any of it puts me into the so-called “Christmas spirit.”

Steve, you seem a little put off by this, why?

Christmas has always been a religious celebration and I take issue with this idea of “taking apart” the celebration in order to make it more politically correct or “acceptable” to a wider range of people. Before modern times when the Christian Church adopted it as one of their flagship holidays, and before Coca Cola and Santa Claus wore the same colours, the actual day of Christmas was kind of in limbo. I’m not going to go into a whole detailed history of the thing (that’s what Wikipedia is for), but let’s just say there were a bunch of different religious/pagan celebrations all around the winter solstice and finally December 25th was selected to be the season of being with friends and family and loved ones. In other words, the day commemorates a deity or deities, be them pagan or Christian.

But, be that as it may, Christmas is shifting and changing again for better or worse and it’s this shift of the Christmas holiday to Asia that makes me wonder if Christmas is changing itself to fit the times yet again as it did so many years ago?

It’s with these thoughts in mind that I decided to take a friend of mine to church on Christmas Eve. She wanted to see what it was all about and, not only that, me being a student of history and a casual observer of cultural traditions around the world, I figured it would be worth it to see what a Christmas Christmas mass would look like. And it would probably make my Mom happy, too.

***

I suppose it was a regular Christmas Eve in Beijing in that everything was stirring, even the mice. I briefly thought about making a traditional Ukrainian Christmas dinner but, since we both worked during the day, I decided to put it off for another time. We opted instead for a turkey dinner at one of the nearby Western-focused restaurants, followed by dessert.

Afterwards, we made our way over to the Wangfujing district to attend midnight mass at St. Michael’s Catholic Church, (圣弥尔教堂 sheng mi er jiao tang), a Roman Catholic Church. Much to my surprise, police cars and uniformed officers stood watch at the intersection at which the church stood and, upon entering into the church grounds, we went through a set of metal detectors and were quickly patted won.

And yet again, I was surprised. It was packed.

Why surprised? Because technically and legally China is non-denominational, meaning it doesn’t have a religion that it follows (for example, the USA has “In God we trust” emblazened on their money, but you’ll find no such thing in China), though the country does study ancient writings, such as the works of Lao Tze and Confucius.

Since the church was packed, my friend wondered if we would have to stand for the mass. Knowing how long these things can go on I had none of that idea and proceeded down the left wing to find an open spot. If someone was trying to reserve a spot that would change as, I figured, in China, first come, first served. It’s the same as the subway system, right? I spotted an empty seat and asked the young couple if we could sit beside them. After briefly glancing at me (I’m certain that if I was Chinese they would have said no), they agreed. There are certain times when it helps to be a foreigner.

As we entered the pew, I instructed my friend on how to cross herself: place the thumb, index and middle fingers on your right hand together (which symbolize the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit), and then touch your forehead, stomach, right shoulder, then left shoulder. I noted that this method is the Ukrainian Catholic version of crossing, not the Roman Catholic. Roman Catholics cross themselves with their whole hand and usually touch their left shoulder first and then their right. I’m not sure if really fully understood but I nod in agreement that she now knows how to cross herself and I’m sure God noticed, too.

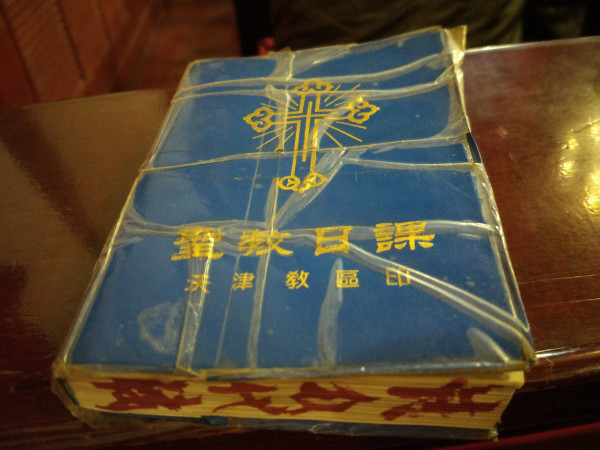

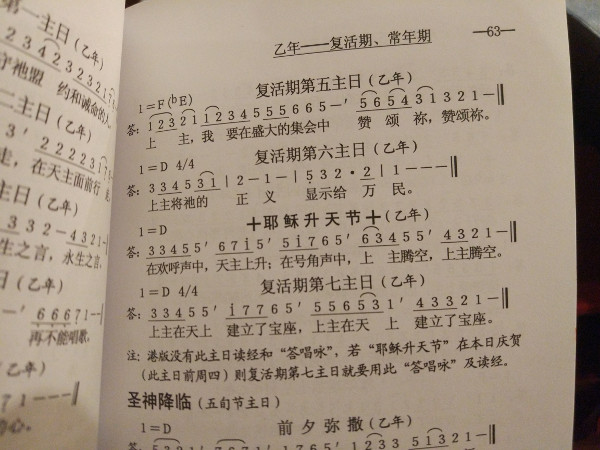

While we waited, we looked through the church books (all in Chinese). Since my friend had never been to church before, she didn’t know what to make of them either. I’m not entirely familiar with the Roman Catholic mass so I couldn’t even skim through to pick out the important parts. What’s worse was that a large pillar was blocking our view of the projection screen so I couldn’t see what pages were being referred to, nor did the couple beside us know. I flipped through the books and took some pictures, using my identity as a foreigner as the reason why I was taking pictures in a church. Since I’ve started travelling, my whole view of taking pictures during religious ceremonies has changed quite a bit and I not only see it as a grand historical gesture to preserve what is today, but also as a remembrance of what I did and to share with the folks back home.

I wasn’t out of place taking photos. In what’s become Chinese fashion, most people played on their phones while waiting for the mass to actually start.

Just after 11 pm, the choir began singing. I think they did a test run first to get their voices prepped, or they were completely off on their timing and pitch. I wasn’t sure which. I thought it would be Chinese but I recognized the words “In excelsis” (Latin for “in the highest”) which, again, surprised me. Here we were in Beijing at a Roman Catholic mass and a Chinese choir was singing in Latin. I wondered if this was still some form of culture shock some three years after arriving in China.

But let me clarify. I say “surprised” but I may not be entirely accurate in my description. Instead, it’s more of a “Ah, so there are other people who do these things” type of amazement; that the things you hear in your hometown in the middle of the Canadian prairies can also be heard on the other side of the world. So, yes, surprised at the number of people, surprised at the Latin, not so surprised by the phones and surprised by…

The singing. Much to my surprise again, it wasn’t just the choir that was singing, the crowd joined in, more properly referred to as “the congregation”. Again, I’ll re-iterate that China isn’t really a religious country and that religion was kinda, well, pushed off to the side for much of the last few decades. But here was a church full of people singing hymns that I could faintly recognize as the same ones sung at St. Ignatius Church in Winnipeg. Interesting.

As the singing began in earnest, the priest made his way under a shawl held by the deacons and other mass-helpers down the center aisle and… out came the cell phones. Mine included. I’m in China, it’s okay to use your cell phone in China anywhere anytime, right? Pictures and videos followed by some heads quickly bowing down low to do what I could only imagine: posting to WeChat or Weibo, China’s main social media networks. The procession was to bring baby Jesus to his cradle under the roof that made up the church’s nativity scene. All the classic elements were there: Mary, Joseph, angels, sheep, three wise men, etc. No Santa Claus, thankfully.

And then I could only guess that the greater ceremony had started because the choir kept singing. This threw me for a loop because in the Ukrainian Catholic liturgy that I’m used to, the priest does a lot of the talking and leading of the service. Here, however, the choir sang a few hymns and then the Little Mary’s (I don’t know what else to call the girls who were dressed in white and there to help the mass but not in the same capacity as the altar boys, who directly helped the priest throughout the mass) did much of the first readings that actually recount the birth of Jesus.

I flipped through the prayer book in vain so I couldn’t even show my friend what would happen next or, more importantly, what was happening. Simply put, it was all Chinese to me and, to my friend, it was all completely foreign to her. We knew that sometimes we had to use the hymn book but we never knew what page to turn to. Sometimes we had to use the big, black, Bible-looking book, but, again, didn’t know what page to turn to despite the guy beside us seeming to know. And forget the little blue book that I could only surmise was the actual prayer book. Didn’t look too Christmas-y to me and it didn’t have the usual layout that I’m used to seeing in prayer books. But, whatever happened, the congregation knew the words and responded in the appropriate tones and sayings. I found this odd because, again, thinking of China as a not entirely Christian country, I expected some bumbling or confusion of what to do, but there was none of it. Straight ahead, on-the-spot responses to whatever the Servants of Mary or the priest or the deacons said.

The priest finally spoke more than just a few words at about 11:33 pm (I could keep track of time because the only thing we had a clear view of was a clock hanging on one of the pillars close by). But only the Lord and the Chinese congregation knew which part that was, I sure didn’t. Thankfully, one of the altar boys had a wood clapper mechanism that he banged together whenever he wanted us to sit or stand or kneel as the case may be.

There were times when the choir seemed off-key but I recall being told that Chinese music uses microtones, something you’ll hear more clearly in Peking Opera. So I wasn’t sure whether or not to accept this as a genuine vocal performance or simply an off-key choir. Despite at least one confused glance from one of the deacons, I’d say it was the latter but, again, maybe that was just a signal of some kind.

At one point my friend asked me about the place where the priest sits on one side and the person on the other. I thought about what she meant.

“You mean the confessional?”

“什么意思?(“What do you mean?”)”

“Where you tell the priest what you did wrong?”

“Yes.”

“Oh… good question.” I looked around the church and couldn’t spot any, but usually the confessionals are located in one of the corners.

She asks if others can hear you when you’re in there to which I say “Probably not”. But it’s China, it may be different?

Then I start wondering where she got her Church knowledge from, so I ask her,

“Where did you learn about all this Church stuff?”

Sex and the City.”

Ah. I see. I can only imagine what else she learned from that show.

In typical church fashion, we sit, stand, and kneel a few more times, each action preceded by a Clap! by the clacker person. Although the three other Chinese bodies in the pew are able to fully kneel when asked, I cannot. My jacket is slung over the pew in front of me which makes it already awkward trying to maneuver. Further, the the pews aren’t nailed to the ground so tend to shift places. They might not move if the Chinese people lean against them but if this foreigner puts any weight on it, the thing will squish the people in the row behind. I do a three-point squat (a “no-no” according to some folks) and content myself that the pew is only inching slowly into the folks kneeling behind us. And then Clap! and we stand up again. Good, cause my quads aren’t what they used to be.

Finally, communion time and I’m curious what the communion bread will be like. I’m baptized and I do say a prayer every now and then so I feel no regret about going up for communion. My friend opts to stay behind despite me saying that she could just get a blessing and not take communion.

I walk to the back of the church to line up behind a few hundred other church-goers. The line moves quickly and I see one or two other foreign faces and hear some French being spoken. Are they here out of duty or curiosity, I wonder. The number of people receiving communion initially leads me to believe that Christianity has quite a foothold in this country, but then I recall that there are people we call “CEOs” in the West, that is, Christmas and Easter Only. That is, they only show up to church twice a year. And often because they’re told to go.

I get to the front and the priest places the wafer into my mouth. It’s like most other Roman Catholic wafers I’ve tried, but thinner and “melts” much more quickly before sticking to the top of my mouth. When I get back to the pew my friend asks me what I ate.

“A wafer of bread. Thinly sliced, holy bread.”

“Ah. Same as in your country?”

“No. I’m Ukrainian Catholic and we often get bread and wine mixed together.”

“Why?”

I quickly go through the whole backstory of why in my own head and decide it’s best to simplify the answer:

“Roman Catholics believe the communion is a symbol of Jesus’ body while the Ukrainian Catholics believe the bread and wine are actually transformed into the body and blood of Christ.”

“Oh, I see.”

I’m not sure she entirely understands and, to be honest, I wonder how these ideas can still exist today.

I kneel and say a prayer for my parents, especially for my Dad, wondering if he’s watching over me. Though I do pray from time to time, I don’t blame people if they don’t. I’ve largely given up exerting too much mental pressure on what happens after death, figuring that I can only live in the now and not worry too much about the past or future, especially as it pertains to how the universe and all its constituents interact. But I digress.

The mass ends around 130 am or so and a few church-goers rush up to the nativity scene to kneel and pray. I tell my friend that she should go look but the crowd kind of scares her. I’m curious so I lead the way. We take a look and I ask her if she knows how to pray. She says no. Thinking this is a teachable moment and that God would appreciate the gesture, I offer to teach her and the Our Father and the Hail Mary with her. God’s smile upon this act may only be dampened by the fact that I had trouble recalling all of the words in the right order since it’s been a while since I’ve said them, especially so slowly.

We exit the church and, while taking a few more photos, decide to take the bus home instead of trying to find a cab at this hour. We walk three lengthy Beijing blocks to the night bus stand and wait in the cold wind. Along the way I tell her that my Dad, brother and me would usually have a shot of scotch and something to eat after we got home from liturgy. We opt for the water that she brought.

The night bus arrives and, curiously, it was full of people, particularly young Chinese men dressed in what looked to be deliverymen attire. Each one of them had a folded-up bicycle beside them and were either napping or staring blankly at their cell phone. I asked my friend who these men were and what they were doing. She responded by saying that these guys were the designated drivers for Christmas evening. Apparently, if you drink too much you can call for one of these guys to show up and drive your car home for you. I’m not sure if you’re in the car too or if you just hand over the keys. As she spoke, one of the guys stood up and yawned. As the bus came to a halt at the next bus station he disembarked, put away his cell phone, unfolded his bike, and then rode off down the designated bike lane.

And with that, so ended another Christmas in China. This one at least included a few more “real” Christmas elements, even if there were no presents involved. At the very least, I did attend midnight mass. I guess if I stay here for the remainder of the year I’ll have lots of time to practice my cooking skills, right?